By Emily Di Natale

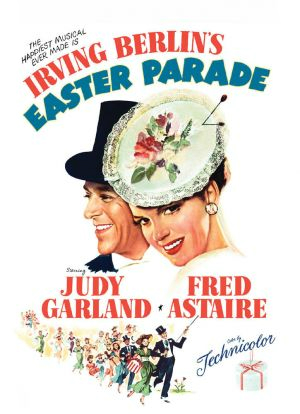

I’ve watched Irving Berlin’s Easter Parade three times in my life. I first sat down to watch it when I was about seven. My only recollection of the film (apart from the fish face that Judy Garland pulls) is my confusion on finding ‘Dorothy’ out of Oz. Her song about home being ‘down on the farm’ was, to my young mind, a rather tenuous link to her life in Kansas. Fast forward approximately ten years. By this time I had come to realize that movies were not real life, and neither was Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz. With this second viewing came the observation that Don Hewes (p layed by Fred Astaire) was pretty old to be pairing up with Hannah Brown (played by Judy Garland). I realized, of course, that the film gets away with it because of Fred’s peerless presence on the dance floor.

layed by Fred Astaire) was pretty old to be pairing up with Hannah Brown (played by Judy Garland). I realized, of course, that the film gets away with it because of Fred’s peerless presence on the dance floor.

I hope that, almost twenty years since my first introduction to Easter Parade, I can offer some reflections on the musical with a little more depth.

What first came to mind on recently watching the film were the strong overtones of Pygmalion[1]. This initially becomes apparent with Don’s assertion that without his coaching, his dancing partner, Nadine (Ann Miller), would have remained an unexceptional chorus girl. This show of arrogance was provoked by Nadine’s sudden declaration that she was breaking their dance partner contract (despite upcoming performances) in order to launch out on her own as a sole entertainer. Furious, and a little bit tipsy, Don makes a bet that he can turn any girl off the street into a brilliant dancer. Enter Hannah Brown (Garland); an amateur dancer who can only tell her left leg from her right with the help of a garter.

On previous viewings, the whole Pygmalion nuance and the related gender-based assumptions had eluded me. This time, however, I was made quite aware that my perceptions of the film as a 21st century viewer would have most certainly differed from those of its contemporary audience, who would not have raised an eyebrow at what I perceived to be some glaring gender no-go zones. For example, the film deemed it acceptable for one of the male singers to croon: ‘The girl I love is on a magazine cover… if I could meet a little girl as sweet I’d simply claim her and name her my queen.’ And of course, there is the sultry antagonist, Nadine, cast as such because she has dared to pursue her own ambition rather than continue to be known as Don Hewes’ dance partner.

The man singing about his magazine woman has his number accompanied by a series of silent and smiling females posing as life-size magazine cover models. The song climaxes with the appearance of Nadine, the sole female dancer who leads a troupe of dancing men. Have the tables turned? … No, it turns out she is the ‘little girl’ who is to be ‘claimed’ and ‘named’ by the other guy. At this point I had hammered the last nail on the coffin of Easter Parade: feminine independence condemned. Then I recalled another scene in the film where a woman is ‘named’ by a man.

Don, desperate to bolster his suffering career and to prove that he can create a great dancer out of a nobody, is remaking Hannah Brown into the exotic Juanita. (His words on first hearing her name were, ‘Oh, we can fix that.’) But, in spite of both his and her efforts, Hannah won’t be remade. Their first performance as ‘Don and Juanita’ exhibits the amateur ‘Juanita’ tumbling ridiculously around the dancing Don.

It is only when the duo finally advertise themselves as ‘Hannah and Don’ that they begin to experience success. Gone are the lavish costumes with their feathered trims which made Nadine glamorous, but Hannah a figure of ridicule. We now see ‘Hannah and Hewes’ perform such numbers as ‘We’re a Couple of Swells’. The comedic song and dance routine parodies social elitism by mimicking the behaviours and ideas of the ‘upper class’ in rough, ragamuffin style, complete with muddy faces and missing teeth. It’s a far cry from Don’s past performances with Nadine, and it’s interesting to note that the performers’ success in this instance comes from accepting Hannah on her own terms; not ‘naming’ or ‘claiming’ but simply recognizing her strengths. In a round-about-way, Hannah is the Pygmalionesque statue that begins to chip away at the sculpture.

This is further emphasized at the end of the film when, following a seemingly irredeemable quarrel between Hannah and Don (who by this stage have fallen in love), Hannah decides to take matters into her own hands on Easter Sunday. She sends Don flowers, a new hat and a live rabbit (thereby mirroring the actions of Don at the beginning of the film, where he purchases extravagant bouquets, a glitzy hat and a toy bunny for the thankless Nadine). Her arrival quickly follows that of her presents. She serenades Don by singing the male part in the song ‘Easter Parade’, including:

I could write a sonnet about your Easter bonnet

And of the guy I’m taking to the Easter Parade

And so the film managed to subvert my assumptions about the assumptions of gender in the Golden Age of Hollywood. Not that I believe that’s what it set out to do, nor do I think that it set out to subvert anything, really, particularly not gender power-play. That’s just me indulging in a little hobby of mine – film and literary interpretation. I’m sorry, I can’t help it; I teach English.

I think it is highly likely that the film-makers intended to provide a bit of fun and entertainment, which Easter Parade most definitely does. One of my favourite parts is a dance routine in which Fred Astaire dances in slow motion while a troupe of cabaret style men and women dance in real time in the background. It is a spectacle well worth viewing.

The gaps between musical numbers are filled in by an enjoyable plot that manages to convince its audience of its sincerity while gently laughing at itself. (See the scene in which Hannah is asked by Don to prove that men turn their heads to look at her in the street. As head after head turns, the camera rolls in to focus on Hannah walking ahead of Don and puffing out her cheeks in an unflattering fish face). All in all, my final comment would be that the narrative is really just an excuse to show off Judy Garland’s incredible vocal cords and Fred Astaire’s phenomenal dancing shoes. And there is everything right about that.

———————————————————————–

[1] Pygmalion was a play written by Bernard Shaw in which a professor of phonetics declares that he can turn an ordinary dirty street girl into a duchess. Named after a Greek mythological sculptor who fell in love with a female statue he created. However the story would be more commonly known by its musical adaptation, My fair Lady.