By Jeremy Ambrose

Warning: The essay below discusses many crucial plot points including the film’s ending. Watch the film first and read the essay afterwards.

There are many ‘serious’ questions that arise from Joel and Ethan Coen’s film A Serious Man. Like the biblical text it is most compared with, the questions are huge, concerning justice, the meaning of suffering and God’s relationship to humanity. I would like to focus on the one question, potentially smaller in scope, that finds its basis in the title of the film, and that is: What does it mean to be a ‘serious man’?

Being a ‘Serious’ Man

Larry Gopnik’s life is falling apart around him. His wife wants a divorce so she can be with another man. His kids fail to respect him. His tenure is in doubt. He is being bribed and blackmailed to change the exam marks of a wealthy Korean student. His brother is in trouble with the law. He is financially insecure and leaking money at every turn. He is bullied into leaving his home and moving into a nearby motel. In the face of all this, he turns to his Jewish faith and asks ‘why?’ He is seeking spiritual enlightenment, an end to the sufferings he is facing and meaning for all he is going through.

The logical assumption is that Larry Gopnik is the ‘serious man’ in question. But in the film, the character actually referred to by that title is Sy Ableman, the well respected but unbearably obnoxious man who Larry’s wife wants to divorce him for. The veneer of respectability, or ‘seriousness,’ covers over without disguising the slimy underbelly of a man whose touchy feely manner emotionally manipulates those around him, controls Larry and repels the audience.

If Sy is a ‘serious man’ it must be according to a worldly standard that has only to do with appearances and not authenticity. He wants to steal Larry’s wife, but he wants to be in good standing with the Jewish community thus requesting she gets a ritual divorce. His sickening over affection towards Larry grotesquely hides the underlying truth that he is responsible for writing anonymous letters intended to destroy Larry’s future job prospects. His self-assured confidence is maddening because we can clearly see the falseness beneath his outward posturing.

Yet Sy Ableman is called a ‘serious man.’ He believes he is a ‘serious man’. Not only has he confounded those around him, but he has confounded himself. Hypocrisy reigns within him such that when he meets his untimely end, in a car accident, it seems to us to be just deserts more than anything else.

But Larry has also had a car accident at the exact same time as Sy, though a non life-threatening one. Larry sees the pattern and tries to make sense of this connection he has to Sy Ableman. He even asks Rabbi Nachtner if God is “telling me that Sy Ableman is me? Or that we are all one, or something?”

The question is pertinent because Larry admits later in the film, that he has tried to be a ‘serious man.’ We automatically interpret that the kind of ‘serious man’ Larry has tried to be is not the same kind of ‘serious man’ that Sy was, yet the connection between the two characters forces one to delve deeper into Larry’s character and contemplate if this actually is the case?

“I Haven’t Done Anything”

What kind of man is Larry? If Sy is a ‘serious man,’ then what is Larry? Throughout the film Larry continually asks “what is going on?” and “why is this happening to me?” In various situations he finds himself, he responds with the words, “I haven’t done anything.” Sometimes the words are said in disbelief, as if he were speaking to himself, other times it is a statement of fact, like when trying to reason his way out of a record subscription. Whatever the context, these words seem to point to Larry’s problem. The words seem true. He doesn’t seem to have done anything.

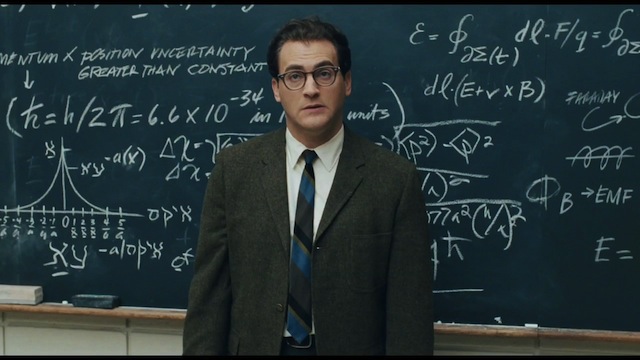

The surprise he shows that his wife wants a divorce shows how disconnected he is from the relationship. It seems he hasn’t ‘done anything’ for his marriage for a long while. His passivity and neutrality may be his way of keeping the status quo, not ‘doing anything’, but his relationships seem to have deteriorated as a consequence. He can’t really speak with or connect with his children. He spends whole classes chalking out intricate looking proofs for the ‘uncertainty’ theorem, but fails to actually have any engagement with his students such that he may as well be speaking to himself. Perhaps he hasn’t done anything wrong, but it does not seem he is doing much right either.

His empty relationships suggest a loveless and soulless existence. His very words, claiming that he has not done anything, convict him. The fruit of his passivity begins to reveal itself and we see within Larry a growing tendency towards sin coupled with a blind hypocrisy which seems at the brink of bubbling over.

Take, for instance, the scene where Larry climbs his roof to adjust the antennae and find clear transmission for the television. The image undoubtedly mirrors Larry’s own desire to tune in to a divine frequency and be able to ‘see’ clearly all that is happening in his life. But while on the roof, he is distracted by his attractive neighbour sunbaking nude in her garden. Seeing him sunburnt in the immediate next scene we know he must have remained on the roof gazing at his neighbour for a substantial period of time and while he may not have actually done anything except passively stand there, the underlying truth is that he has indeed done something, that is, taken a step towards adultery, perhaps even committing it in the heart already.

Larry’s passivity does not allow him to move forward, instead, we witness him sliding backwards. He seems to be moving in the same direction, be it in increments, as Sy Ableman, who must have begun his own slide long before. Soon enough Larry is taking further steps towards adultery, turning up at the door of the woman in question and even getting stoned with her. We see him following in Sy Ableman’s footsteps, walking towards sin. Even his confused passivity in keeping the bribery money leads to the climactic and morally problematic decision of changing the Korean student’s exam mark. It seems such a little act, simply involving the stroke of a pencil, yet the repercussions seem immediate. Unlike in the Book of Job, there seems to be a ‘cause and effect’ type of divine justice at work here. The mystery of it is no clearer to Larry.

Sy has sought to cover over his own corruption and hypocrisy by being a ‘serious man’ and Larry seems to be just as blind to his own slide, believing in his efforts to be a ‘serious man.’ Both fail to understand what it means to be a ‘serious man’ in the sight of God rather than the world. The car accident is not the only connection between them, but the effect of it seems to be in some sort of proportion to each man’s state of corruption. Sy’s accident leads to death and Larry’s to further financial strife. It is as if a warning has been offered to Larry, with the clear consequences of the path before him laid bare. If these are divine punishments then they seem according to specific instances of human sinfulness. Larry, however, struggles to recognise the pattern. The questions asked here are substantially different, then, from those asked in the Book of Job. Job’s argument is that there is no pattern, so what is God playing at? Larry thinks he is asking the same question, but the answer he needs is different because his state of life, or shall we say ’seriousness,’ is fundamentally different to the Job of the Bible.

God Answers the ‘Serious’ Man

The biblical Job is presented as an authentically ‘serious’ man, that is, one who lives according to God’s law with the right seriousness regarding it. Job’s questioning of God can only hold weight because he is a just man who appears blameless in the sight of God. When Job is struck down by afflictions there seems to be no discernible correlation between sin and the personal disaster he faces. Job’s three friends accuse him of sin and seek to interpret his afflictions as divine punishments, thus destroying Job’s reputation and like vultures, await the logical division of his remaining legacy. In misrepresenting Job, his friends also seek to misrepresent God. They finally resort to the argument that God’s justice is unknowable because God is unknowable, basically saying we can’t expect God to be just as we understand that word. His power surpasses our notions of justice. Under this system, God becomes a frightening tyrant whose ways can never be trusted[1].

Job’s friends in the Bible are like Sy in the film, claiming to be ‘serious’ men but really hypocrites at heart, seeking the destruction of another and pursuing worldly gains for themselves under a warped idea of divine justice. Job is the true ‘serious man.’ He cannot accept that God is unjust and God rewards his authenticity and faithfulness by speaking personally to him. The answer to Job’s questions is not what is important, rather, it is the fact that God answers[2]. It is God’s very presence that answers the depths of Job’s probing, as he knows that God is in relationship with him and he has not been forsaken. Sure, he cannot understand why this has happened to him and God does not seek to explain it, but he knows God loves him and he in turn loves and honours God. God speaks from the whirlwind and Job takes comfort in the speaking. He tells Job what we already know (as we have been privy to the book’s prologue with Satan’s challenge) that as mysterious as God’s ways can seem, He is a just God, and the most important thing is right relationship with Him. Job hangs on to God and in doing so he hangs on to love and that is ultimately what satisfies him at the end of the book.

Like Father, Like Son

We have already explored how Larry, unlike Job, lacks righteousness in the eyes of God. Rather, we have seen a closer linking of him to Sy Ableman. But there’s another character closely connected with Larry, more naturally so and this connection is emphasised right from the film’s opening credits. In a scene intercut with Larry’s check-up by a doctor, we are introduced to Danny, Larry’s son. We hear the song Danny is listening to, Jefferson Airplane’s ‘Somebody to Love,’ on his transistor radio and we see the Hebrew teacher confiscating this radio when it becomes apparent Danny is indulging in the music instead of paying attention to the Hebrew lesson. This is just the beginning of Danny’s problems as we learn there was $20 tucked away in the radio’s pouch, money Danny owed to another larger boy and whom he spends the rest of the film running away from to avoid being beaten up. In many ways Danny’s story runs parallel to Larry’s. He is just as disconnected from the family and his only communication with his father concerns the television being fixed so he can watch ‘F Troop.’ He smokes pot, even under its influence at his Bar Mitzvah and seems superficial and irresponsible, like the other children his age. In some way, we can see Danny walking in the same direction as his father. The circuit appears unbroken for the son to one day be just like the father. Their destinies seem entwined with each other and it is fitting then, that the answer Larry has been seeking throughout the whole film, is given to Danny, by the elusive Rabbi Marshak.

Double Vision

Larry keeps asking “what’s going on?” He wants to know why God has allowed all these sufferings and tribulations into his life. Even though he is seeking God’s answer, his vision is limited to being a worldly one. His idea of being a ‘serious man’ is also of a worldly nature and his gradual decline into sin reveals this. He struggles to see through the ‘other’ lens. The film constantly draws attention to a double vision of things, but Larry remains fixed on one plane only. I would argue that the Yiddish prologue to the film establishes this double vision of seeing. Is Reb Groshkover a dybbuk, or simply a once dying man now recovered? The difference between the two answers could be the difference between a spiritual and a worldly reading of events. Even the references to Schrödinger’s cat emphasises a double vision, two ways of seeing that exist simultaneously, the cat being alive and the cat being dead.

Perhaps a little more obviously, the first two rabbis that Larry speaks to also present this mysterious sense of double vision. The first rabbi, though sounding glib, does ultimately tell Larry he has to learn to look at things on another plane. He uses the mundane image of the car park and though he misrepresents God in a similar way to Job’s three friends, he also unknowingly points towards the reality we will witness in the closing frames of the film; the car park taking on a sense of divine awe and ‘fear of the Lord’ as the whirlwind approaches. The second rabbi tells the story of the Goy’s teeth. This strange, mysterious, possibly supernatural happening of the words “help me” written in Hebrew on a non-Jewish man’s teeth is given a very ordinary take home message: it couldn’t hurt to help others. Again, this rabbi, like Job’s friends, refers to God’s unknowability, arguing that we aren’t owed any answers, but he also happens to shine a light on how God can speak to us. He begins his story asking the question “how does God speak to us?” and although he doesn’t return to the point, his story illustrates that God can speak through anything, even the teeth of a Gentile! The ordinary reveals the extraordinary just as the extraordinary can sometimes have very ordinary practical results (like simply helping others).

God’s Answer in ‘A Serious Man’

These two pieces of advice, once stripped of their obvious flaws, provide an interpretative tool by which to read the third rabbi’s words, which as we mentioned above, is given to Danny rather than Larry. Rabbi Marshak, the very emblem of wisdom to the community, speaks to Danny using the language proper to the boy. He returns his radio and then begins to quote the lyrics of the song Danny had been listening to, “When the truth is found to be lies, and all the hope within you dies,” breaking off and adding the question, “then what?” He cryptically names the members of the band and pushes the confiscated radio slowly across the table returning it to Danny. He closes with one last instruction, “Be a good boy.”

Like much wisdom, the words seem too simple to be profound and too profound to be simply understood. But taking the lessons from the other rabbis, if the most profound truths can be found in the most mundane of things and if God can use anything to speak to us, then perhaps the members of Jefferson Airplane unknowingly have performed the role of the Old Testament prophet and have spoken the words of God? Marshak hones in on the quoted lyrics and in doing so, summarises the human condition as experienced by Larry and pretty much everyone that ever existed… When all that the world promises you falls apart, bringing you to the brink of despair, then what? The answer arrives in the final scene, like in the Book of Job, from out of the whirlwind. As the whirlwind approaches the audio fades up on Danny’s radio and we hear the chorus of the song, the same words we already heard in the first scene but now given to us in the right context to understand, “Don’t you need somebody to love… You better find somebody to love.”

Love seems to be the answer offered and it is love that Larry seems to have been lacking in his attempt to be a ‘serious man.’ It is the summary of all the commandments, which can be whittled down to five simple words, “love God and love neighbour.”

You need somebody to love. You better find somebody to love. Can Larry’s trials and tribulations be a divine urging to seek and cling to love, turning away from the Sy Ableman way of self-righteous hypocrisy? Or like the Goy’s teeth, are these happenings really inexplicable and yet, God offers something through it that can’t hurt, an invitation to love in the midst of life’s disasters?

Be a good boy. To be good is not simply to appear good. To be authentically good is to choose the way of love. It is the only way. Like the Commandments, love is an instruction given, a verb to be done. In the Christian context, however, the answer becomes a person. ‘God is love’, the New Testament proclaims[3]. Returning to Job, his questions are not responded to with answers and explanations, but rather, God reveals Himself as the Answer. Job is given the ‘Answer’ not the ‘answer’[4]. Perhaps a similar thing is glimpsed via the Coen Brothers? Perhaps the answer is not simply an instruction to “find somebody to love” but rather an introduction to Love incarnate, to God himself? Perhaps being good is connected to knowing Goodness personified?

To know God, then, would be to know Love. Unlike Larry, Love never produces passivity because to know Love is to bear the fruit of love. The theme runs throughout the bible, from beginning to end, the very word “knowing” expected to be something that lead to generation. The original command to “be fruitful and multiply”[5] takes on deeper meaning alongside the advice that “a tree is known by its fruit”[6] and the final warning that the fig tree without fruit will be “withered at once.”[7]

Being ‘a serious man’ may not be enough to count in this world or the next, but being a loving man may just be everything.

[1] Robert Tilley, “That Which I Greatly Feared” Theology and Terror in the Book of Job, Reader for Hebrew II, CIS, 2011, pp 24-41

[2] Tilley, “That Which I Greatly Feared” Theology and Terror in the Book of Job, p 77

[3] 1 John 4:16

[4] Tilley, “That Which I Greatly Feared” Theology and Terror in the Book of Job, pp 79-80

[5] Gen 1:28

[6] Luke 6:44

[7] Matthew 21:19